ECOLOGY ▪ EDUCATION ▪ ADVOCACY

An Indiana Native

Acer: Latin name for “maple tree.”

Negundo: Latin word derived from Sanskrit nirguṇḍī; a name for the Chinese chaste tree (Vitex negundo); so applied due to the resemblance of the leaves of the two species.

ay-sur nuh-guhn-doh

Ash-leaf maple, ashleaf maple, box elder, box-elder, boxelder maple, elf maple, maple ash, Manitoba maple, poison-ivy tree.

Mature Size & Appearance: Medium to large typically reaching 15–27 m (50–90 ft), but occasionally to 38 m (125 ft). Trunk diameter averages 60–90 cm (2–3 ft) at maturity but can grow as large as 1.5 m (5 ft). The upper branches sweep upward to form an oval to rounded crown.

Bark: Bark color ranges between light brown to pale gray as it matures with interlaced shallow ridges when young that become deeply furrowed with age.

Leaves: Pinnately compound, opposite leaves 13–30 cm (5–12 in) long are oddly pinnate with usually 3–5 leaflets, but occasionally 7–9. The irregularly coarse to lobed margined leaflets vary in shape from oval to ovate to lanceolate, and range in length between 5–12 cm (2–4 in) and between 2.5–6 cm (1–2.5 in) wide. The lateral leaflets are born on short petioles and are attached to a slender rachis that often becomes reddish at maturity. The upper surfaces of the leaflets are light green, and mostly glabrous, while the lower surfaces are a paler, grayish-green, and slightly pubescent, particularly along the veins.

Fall Color: Not particularly showy. Leaves turn a pale, dull yellow in autumn and drop early.

Twigs: Moderately slender, smooth green to olive turning brownish/purple with age with conspicuous white lenticels. Twigs vary from shiny to sometimes covered with a frosted, waxy, glaucous coating. Large leaf scars are crescent-shaped and nearly surround the circumference of the twig.

Buds: Terminal buds are approximately 5 mm (.19 in), covered with white hairs, and blunt; lateral buds flattened along the stem.

Flowers: Unisexual, dioecious flowers appear before or with the leaves in April–May. Flowers of both sexes are greenish-yellow and have 5-lobed, hairy calyces. Male flowers contain 3–6 stamens, 5 sepals, and are born on long, slender, hairy pedicels. Female flowers, which hang in dangling bundles, have a single pistil with a deeply-forked style, a hairy ovary, and reddish sepals. Flowers are wind-pollinated.

Fruit: As with all maples, boxelder fruit consists of a single seed with an attached wing called a samara. Boxelder samaras, which are 2.5–5 cm (1–2 in) in length, appear in mid-spring in V-shaped pairs that hang in drooping clusters. The seed ripens in the fall, but the samaras are often persistent on the tree through the following winter.

Life Expectancy: Boxelder trees have a life expectancy of approximately 60–100 years. Growth is rapid for the first 15–20 years and slows afterward.

Key Characteristics: When identifying boxelder, look for the following characteristics:

Similar Species: Boxelder (Acer negundo) is one of 5 species of maple trees that are native to Indiana, but it is the only species with compound leaves. The shape and patterning of the leaflets often cause young boxelder trees to be mistaken for poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) and wafer ash (Ptelea trifoliata). Observers can easily separate boxelder from the two by looking at the positioning of the leaves, which are opposite and not alternate on the stem.

Taxonomic Variations

Some taxonomists recognize 2–3 subspecies of Acer negundo, none of which are currently accepted by the Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS). However, there are seven acknowledged varieties:

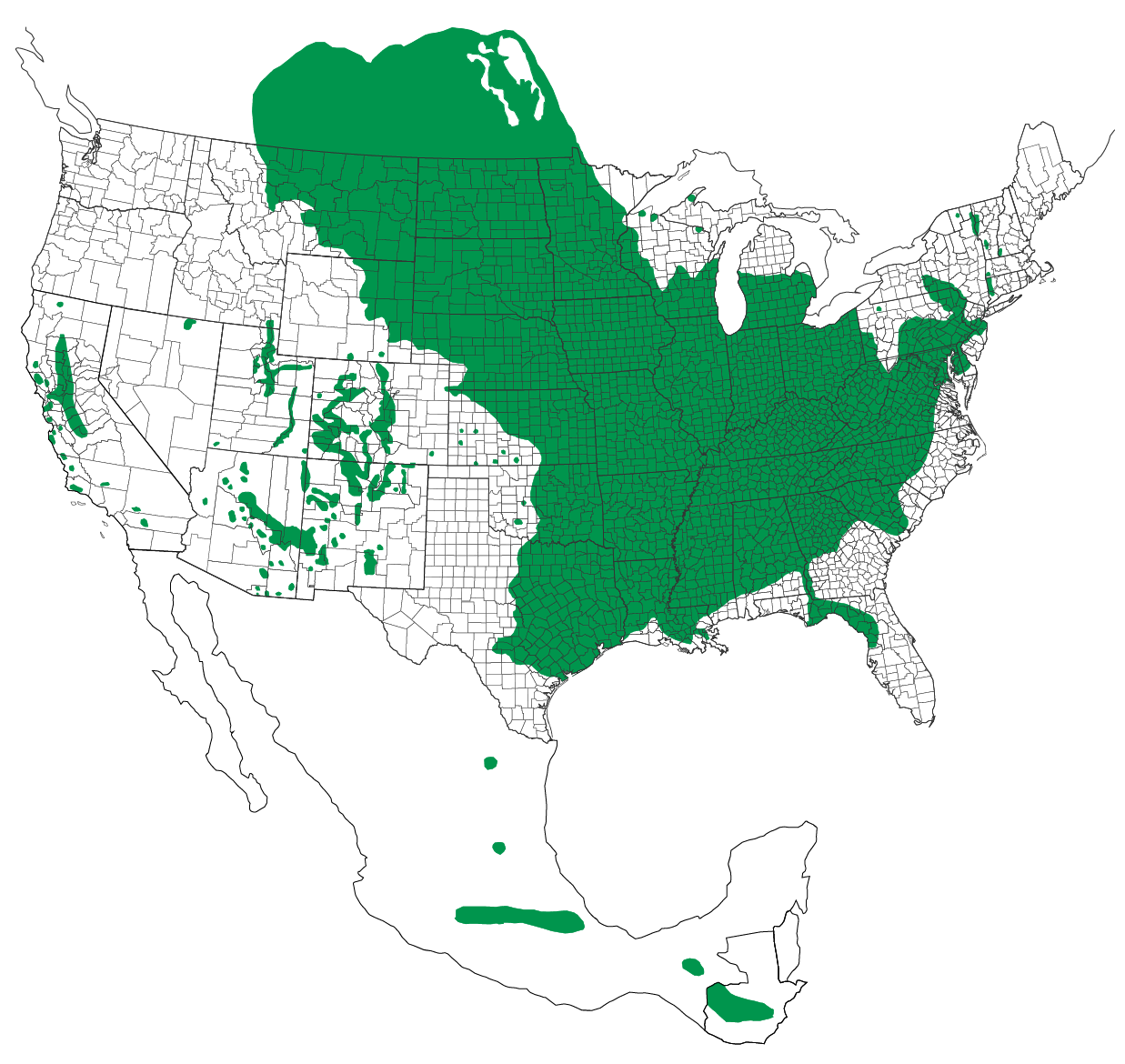

Boxelder is a native North American species that is found from Canada in the north to Central America in the south, and its range stretches from the Pacific to the Atlantic. Europeans, Asians, and Australians have introduced boxelder to their respective continents where it has become naturalized, and in Australia, it is considered an invasive species. Boxelder is native to every county of Indiana.

Acer negundo — Native Range

|

Species native and present in county |

Boxelder is tolerant of a wide range of soil conditions but is most frequent in nutrient-rich, moist soils including floodplains, and along the edges of lakes, ponds, streams, and swamps. In uplands, it occurs less frequently, often along fencerows and woodland margins. Boxelder is intolerant of deep shade.

Culinary: Although boxelder (Acer negundo) has a lower sugar content than other maples (Acer spp.), (Conger 2019) native Americans had several uses for the processed sap. The Cheyenne mixed it with pieces of animal hides to produce candy (Moerman 1998). Western tribes such as the Sioux, Omaha, Navajo, Montana Indians, Kiowa, Western Keres, and Dakota also used the sugar in candy and as a flavoring additive to foods and beverages (Moerman 1998). Early settlers to the western plains also boiled the sap of boxelder into syrup for use as a substitute for cane sugar. Boxelder is said to have been one of the few sources of sugar on the American prairie (Northern 2019).

Functional: Due to its softness and susceptibility to rot, boxelder wood had limited uses. Native Americans, however, developed adaptations for seemingly all plants, and boxelder is no exception. Perhaps the most common native use for boxelder wood was for firewood and charcoal, including charcoal for ceremonial painting and tattooing. Various tribes used boxelder wood for other specialized purposes, including bowls, drums, pipestems, and prayer sticks (Moerman 1998).

Medicinal: Native Americans found several medicinal uses for boxelder’s inner bark. The Meskwaki and Objibwa used it in various ways to induce vomiting (Moerman 1998), and other native American tribes used it to treat respiratory conditions, kidney infections, paralysis, and swellings, and other ailments. European settlers used varying dosages of the inner bark of the tree to both reduce and induce vomiting, and also in a wash to treat maladies of the skin (Foster and Duke 1990).

Culinary: Boxelder sap is still occasionally boiled down into syrup.

Functional: Since the arrival of the Europeans in North America, boxelder has never had much commercial value. It was and still is used for crates and boxes, in pulp for paper, for fuel, cheap furniture, and kitchen tools. Woodworkers occasionally use boxelder wood, particularly gnarled pieces or those with red-stained spalting, for turning into bowls and other objects.

Medicinal: The authors have found no additional contemporary medical uses for boxelder.

Landscape: Thanks in part to their fast growth, in years past, boxelders were commonly planted as a midwestern street tree. However, due to their weak wood, copious amounts of seed, and irregular shape, they are no longer planted by most urban foresters. Some municipalities have gone even further and have legally prohibited boxelder trees from being planted along city streets. Although boxelder is not common nursery stock, several cultivars exist including:

Despite being rarely sold in nurseries, due to their prolific seed production and tolerance of poor conditions, boxelders remain common urban trees.

Perhaps the most intriguing folklore comes from the apparent origin of the vernacular name “boxelder.” According to most sources, Europeans settlers derived the “box” portion of the name from the resemblance of the soft, light-colored wood to that of the European evergreen shrub known as “common box”(Buxus sempervirens)(Line 2008). Others attribute it to box making, a frequent application for the wood (Ohio 2019). “Elder” came about because of the likeness of the leaves to those of the European elder (Sambucus nigra).

Boxelder seeds contain Hypoglycin A, an amino acid that is toxic when ingested. Studies have linked Hypoglycin A to Seasonal Pasture Myopathy (SPM), a potentially fatal disease in horses (Guthrie 2019). Since horses do not typically consume the seeds of boxelder, owners and caretakers can minimize risks by supplying supplemental sources of food and by ensuring that pastures are not overgrazed (Hammer & Zeleznik 2013).

The only known Indiana place names for the boxelder tree are streets located in Carmel, Indianapolis, and Whitestown.

Vanderburgh County: Michael Agee & Vanessa Wendall, 2055 E. Florida St. Evansville, IN 47711 - Circumference 156 in, Height 70 ft, Crown 60 ft.

In Indiana, boxelder is a source of food to most of the same fauna as other members of the maple (Acer) genus including at least 84 species of native moths, 10 birds, 11 mammals, and various additional insects.

| Known Mammal and Bird Associates in Indiana | ||

| Taxonomic Name | Common Name | Parts used |

|---|---|---|

| Class Aves (Birds) | ||

| Bonasa umbellus | Ruffed Grouse | buds, twigs, and seeds |

| Coccothraustes vespertinus | Evening Grosbeak | seeds, buds, and flowers |

| Colinus virginianus | Northern Bobwhite | buds, twigs, and seeds |

| Haemorhous purpureus | Purple Finch | seeds, buds and flowers |

| Meleagris gallopavo | Wild Turkey | buds, twigs, and seeds |

| Pheucticus ludovicianus | Rose-breasted Grosbeak | buds, twigs, and seeds |

| Sitta canadensis | Red-breasted Nuthatch | buds, twigs, and seeds |

| Sphyrapicus varius | Yellow-bellied Sapsucker | sap |

| Spinus tristis | American Goldfinch | seeds, buds, and flowers |

| Zonotrichia albicollis | White-throated Sparrow | seeds, buds, and flowers |

| Class Mammalia (Mammals) | ||

| Castor canadensis | American beaver | seeds, flowers, bark, and twigs |

| Glaucomys volans | southern flying squirrel | seeds, flowers, bark, and twigs |

| Microtus pennsylvanicus | meadow vole | seeds |

| Odocoileus virginianus | white-tailed deer | twigs and foliage |

| Peromyscus leucopus | white-footed mouse | seeds |

| Procyon lotor | North American raccoon | seeds, flowers, bark, and twigs |

| Sciurus carolinensis | eastern gray squirrel | seeds, flowers, bark, and twigs |

| Sciurus niger | fox squirrel | seeds, flowers, bark, and twigs |

| Sciurus vulgaris | red squirrel | seeds, flowers, bark, and twigs |

| Sylvilagus floridanus | eastern cottontail rabbit | seeds, flowers, bark, and twigs |

| Tamias striatus | eastern chipmunk | seeds |

| Ursus americanus | black bear (extirpated) | seeds, flowers, bark, and twigs |

The insect most commonly associated with boxelder trees is the boxelder bug (Boisea trivittata). A specialist on boxelder and other maples, in spring, adult boxelder bugs lay their eggs in the crevices of the bark. After the eggs hatch, the nymphs feed on the juices of the leaves and on developing seeds. Boxelder bugs do not cause long term damage to the tree, but their tendency to overwinter inside of homes and other structures earns them the reputation of being pests. When threatened, they emit a smell that is distasteful to would-be predators. Despite that, they are a food source for chipmunks and other animals.

Boxelder is subject to many of the same diseases that are common to other maples (Acer spp.) including:

Propagation requires cold stratification. Collect the samara as soon as they fall. Some sources suggest removing the papery seed covering for better germination. Soak the seeds in water for one day and then place the seed in a cold frame or sealed container in the refrigerator for 2-3 months. Plant seeds in early spring in 1 cm (3/8 in) of soil. Protect the seed from wildlife. Germination should take place in the spring. Boxelders may also be propagated asexually through softwood cuttings and by layering.

In addition to the main GAINTP bibliography, the authors have used these additional sources:

The Ohio State University. c2019. Boxelder (Acer negundo). Ohio Perennial and Biennial Weed Guide. [accessed 2019 Jul 13]. https://www.oardc.ohio-state.edu/weedguide/single_weed.php?id=11

Conger A. 2019. A Comparative Analysis of Sugar Concentrations in Various Maple Species on the St. Johns Campus. [accessed 2019 Jun 20]. https://employees.csbsju.edu/ssaupe/CV/conger_final_report.pdf

Foster S, Duke JA, 1990. A field guide to medicinal plants eastern and central North America. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company (Peterson Field Guide Series).

Gilman E, Watson D, 1993. Acer negundo ‘Elegans’ Fact Sheet 21. Gainsville, FL: University of Florida.

Guthrie T. 2019. Boxelder trees are toxic to horses. MSU Extension. [accessed 2019 Sep 26]. https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/boxelder_trees_are_toxic_to_horses

Hammer C, Zeleznik J. 2013. Boxelder Seeds Toxic to Horses. Ag.ndsu.edu. [accessed 2019 Sep 26]. https://www.ag.ndsu.edu/news/newsreleases/2013/sept-9-2013/boxelder-seeds-toxic-to-horses

Line L. 2008. A Tree of Too Many Names. National Audubon Society. [accessed 2019 Jul 13]. https://www.audubon.org/news/a-tree-too-many-names.

Northern University. 2019. Boxelder (Acer negundo). www3.northern.edu. [accessed 2019 Jun 20]. https://www3.northern.edu/natsource/TREESA1/Boxeld1.htm

Osorio R. 2019. Acer negudo (Box-Elder), an Overlooked Native Tree. Fnpsblog.blogspot.com. [accessed 2019 Sep 25]. http://fnpsblog.blogspot.com/2010/07/acer-negudo-box-elder-overlooked-native.html

Steinman H. 2012. Box-elder. Phadia.com. [accessed 2019 Sep 26]. http://www.phadia.com/fr/5/Produits/ImmunoCAP-Allergens/Tree-Pollens/Allergens/Box-elder-/

Texas A&M Agrilife Extension. 2019. Boxelder | Texas Plant Disease Handbook. Plantdiseasehandbook.tamu.edu. [accessed 2019 Sep 25]. https://plantdiseasehandbook.tamu.edu/landscaping/boxelder/?fbclid=IwAR1OjZOLXFMuy5ZS0d0-1kIBzY0CNdAALgU-gk0HK8aqQJQY7DlDLLm8lUQ